The Sportsman’s Bar and Academy Billiards were popular spots with Hankish and his “handlers,” according to three former employees.

My wife and I have heard many stories during our lifetimes. She grew up in South Wheeling and Wheeling Island, I spent my youth in the Woodsdale section of Wheeling, and we both went to high schools where “spot sheets” were readily available. We both knew where to go and where not to go, and we knew many men whom we refer to as “in the game.” We knew the names and the faces from working at places like Elby’s and Wheeling Downs and from patronizing establishments like the Esquire and the Sportsman’s and the Flamingo.

Our children, though, know nothing of the organized crime culture that once thrived in their hometown, and while we were born in the 1960s, they entered the world in the early 1980s. The activity still took place, of course, into their teen-age years, but it was not so prevalent that it entered into everyday conversation as it once did. They did know about the illegal poker machines but only because they were always pleased when Mom and Dad would win.

Once Lias ran the town because he owned the rackets and the racetrack. As the story goes, he ruled his criminal circuit with an iron fist while also contributing to the community’s needy. Following his death in 1970, “No Legs” Hankish took over, and his reach extended into western Pennsylvania, East Ohio, to Point Pleasant, and reportedly beyond. A lot of people booked bets, several smuggled drugs (mostly marijuana, some pills, and cocaine into the mid-1990s), and people did get whacked.

And yes, that does mean murdered. Some of the victims were found, and some guys just vanished. If you lied to Lias or Hankish, they “wrote you off” the bookies agreed. But if you stole from either of them?

“Some of us wonder why anyone would keep trying,” one former participant explained. “Lying was one thing. That just got ya tossed out. But stealing and talking to cops never turned out good for the guy breaking the rules.

“Otherwise, there were territories, and people knew the lines. If you wanted to place a bet, we had to know you. It was a process. It was a trust thing, and we were always told not to take chances because the feds were always smelling around.

“There were some corrupt cops back then, too,” he continued. “Some in Wheeling, and a lot in other areas, but not all of them. I know some people think that about the cops from back then, but it wasn’t all the cops. Just some, but usually the right ones.”

There were full-timers under both kingpins, like the handicappers, the muscles, and the top bookmakers, but both organizations involved everyone from the bet-taking barkeeps to the corner call girls. These guys worked under Hankish only, and they agree he set different rules from those he chose to live by.

“No drugs, only a little drinking, and no talking – the same rules we heard Lias had,” a former bookie told me. “Those were Paul’s rules, too, but that’s not how he lived later in his life. He was smart. Very smart. But he was also very vicious, especially in his later years in Wheeling.

“At one time he was probably in the top five on the East Coast as far as the business is concerned, but it got to the point where he had to start making his phone calls on pay phones in department stores because he got careless,” he said. “Once they put him away, he was furious, and he turned on a lot of people who were close to him.”

Missy Ashmore with Kennen & Kennen Inc. leads many tours to this floor, the site of the last major bookmaker bust in the mid-2000s.

After Hankish was convicted of extortion, drug trafficking, gambling, and tax evasion and was sent to federal prison, he composed several letters in which he implicated many former associates and lifelong adversaries. There are a lot of names listed in those letters, most of whom were gamblers with no push and no power, but they had plenty of cash and a lot to lose.

“He was furious because people talked,” another former bookie said. “No one was supposed to talk, but the operation attracted so much more attention because of the drugs. That’s really why the feds got involved. The drugs.

“When quaaludes became popular, that caused a lot of trouble for everyone. The coke was bad enough, but everyone wanted those pills. I always thought all quaaludes led to was people having sex at night and then immediately regretting it in the morning.”

But once Hankish was jailed, there was no one to follow as “No Legs” did Lias. Instead, these oddsmakers tell me, everyone stayed to themselves, worked their own action, and did what they could not to attract attention.

“A lot of the guys just kept their own and didn’t say a thing about it just like now,” the wise man said. “We still had some of the machines, the books, and some of the drugs, and that was enough. No one wanted to get involved like that again, and then (the state of) West Virginia legalized the machines so they could get their share.

“Except for the prostitution and the drugs, everything most of us were doing back in those days is now acceptable at fundraisers these days,” he said. “Betting your money is betting your money, so the government figured out how to take most of the action. They didn’t take all of it, but they took the bulk of it.”

It was Jan. 17, 1964, when a 32-year-old Hankish got into his Studebaker outside his Richland Avenue house in Warwood. It was probably dynamite that spread debris as far as 150 feet on that morning. Hankish lost his legs, but not his life.

Tom Burgoyne was assigned to Wheeling by J. Edgar Hoover in June 1967, and it took him only three days to hear the name Hankish, and he would follow the rumors and tips and evidence for nearly 30 years before finally bringing the federal charges against him. Burgoyne agreed with the bookies about the business after Hankish went to prison.

The state stole the video poker business. The bookmakers downsized. And the mob, as it was organized under Lias and Hankish, was gone.

“That didn’t just happen here; it happened all across the country at that time,” the former federal agent said. “There was a lot of pressure by federal law enforcement on gambling back in those days because the information was so easy to come by, and that was because it was widely accepted as a way of life.

“The public’s opinion about gambling has never changed, really, but the laws were the laws, and it was our job to enforce them,” he said. “But after Hankish, everyone just held onto their own, and they still do it today.”

On Burgoyne’s third day in Wheeling, the local FBI veteran Dick Jones was at the agency’s Quantico headquarters, and the other agent did not care for the young, brash New England native. Burgoyne’s office, though, received a teletyped alert that a tractor trailer stocked with Stroh’s beer was hijacked in Huntington, transported to Bridgeport, and then hidden away in a few different garages in East Wheeling.

Burgoyne, local law enforcement, and the state police found the stashed brew and even those who perpetrated the crime, but they could not make a direct connection to “No Legs.”

“He was smart, Paul Hankish was,” Burgoyne admitted. “He’s a guy who, if he didn’t get so wrapped up in organized crime, that I always believed could have been a CEO for some big company. He was that smart.

“But all three of the guys involved went to prison on federal interstate crimes, and all three were connected to Hankish. We knew it, but not one of them would talk about Hankish,” he said. “Others did, though, and I met with informants. I met with a lot of informants, and some of them ended up dead because somehow someone found out that they talked.”

Not one of the former bookmakers wanted to discuss the career of Jimmy Griffin. Individually they refused because they liked him, and they had to back in those days because he was one of Hankish’s drivers and enforcers. You stayed on Jimmy’s good side, and as long as you did, he was your friend.

Burgoyne has several clear recollections of Griffin dating back to the former federal agent’s third week in Wheeling.

“I saw him on the corner near Elby’s when it was on 12th and Chapline, so I walked right up to him and poked him in his left shoulder,” he said. “I was a brash guy back then; I admit it. I said to Jimmy that it was my job to get him.

“He was a stone-cold killer, and he was a bad person his entire life – even back in high school. He was a guy who would just punch people in the face for no reason at all. He was the enforcer. He was one of those types of guys,” he continued. “After we sent him to prison up in Pittsburgh, I went to see him one last time because Hankish was about to go on trial, and I wanted to see if he had anything to get off his chest. He was dying of cancer when we arrested him, and he was in pretty bad shape when we saw him in Pittsburgh that day.

“They brought him into the Warden’s office, and I asked him if there was anything he did for Paul that he wanted to tell me about before he passed. He said he had nothing he wanted to say and asked to be excused. About halfway to the door, he turned to me and said, ‘Remember when you told me that one day on the corner that it was your job to get me?’ I answered yes, and then he said, ‘Well, I guess you got me.’ He died shortly after I saw him that day.”

Burgoyne worked in Wheeling, but he also lived in Wheeling. He and his bride, Kathy, raised three children in the Dimmeydale section of Wheeling, and he was a little league coach, active in the St. Michael Parish, and he and Kathy socialized, too.

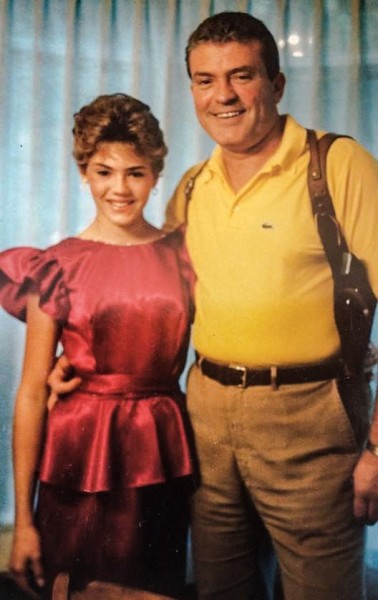

Retired FBI agent Tom Burgoyne poses with his daughter Erin before she attended a formal dance in the late-1980s. Erin did report that Tom removed his firearm before answering the door when her date arrived.

“We would go to the Esquire from time to time, and most of the time there would be Paul Hankish sitting with his boys at the corner table by the bar,” he recalled. “This one time the waitress brought me a drink and said it was on Paul, so I immediately sent a drink back to him. We all knew who was who. It was a game, really. They did what they did, and we did what we did. And it’s the truth; they won most of the time.

“He had action in western Pennsylvania, in East Ohio, and here in the Wheeling area. He was also connected to the people in Steubenville and down south in West Virginia and on the Ohio side,” Burgoyne reported. “One thing was true with everyone, even me and the other federal agents, and that was his rule with his guys about drug use. It changed when he got more involved with drug dealing in the late years, but in the beginning of my years here in Wheeling, that was something even we respected.”

None of the three bookies expressed anything positive about Burgoyne. Two of them told me they refused to be in the same room with him. All of them said they did not vote in Burgoyne’s favor when he won twice and lost once in races for Ohio County Sheriff.

Burgoyne wasn’t surprised. He was the law, and they were the lawbreakers. They had their job, and he had his, and they all took their livelihoods very seriously.

“But I never thought that I was public enemy No. 1 with anyone, not even to the guys who were breaking all of the laws,” Burgoyne said. “I mean, I realize they didn’t like me much while they were getting arrested, but that was always their fault.

“The only time I thought about that was just before the Hankish trial started in 1990. There was information out there that he was going to try to blow up Kolibash’s car and my car. It even made the headlines in the local newspapers. The feds alleged that he had plans to blow up our cars, but I didn’t know anything about it before they issued the statement,” he continued. “That supposedly came from Jesse Anderson, who was also in the enforcer role like Griffin. They were bodyguards and drivers for Paul, but to this day, I still don’t believe it was true. Jesse Anderson told the investigators that he was the one who stopped the bombing. He said to Paul that it was crazy to try such a thing.”

It wasn’t the “Mafia” in Wheeling, Burgoyne insisted, and he splits the same hair those in the business split during the organized-crime years in Wheeling; if it’s not led by an Italian family, it’s not a “Mafia.”

Instead, it was the “mob.”

“They all always insisted there was a difference in the amount of loyalty between the two because the Mafia was more of a family thing, but the mob was a bunch of unrelated people acting like a family. They always told me there was a big difference there,” he said. “At least it made a difference to them. It didn’t to me. Crime is crime to me. Always has been.”

It was a business owner from the corner of Richland Avenue and Warwood Road that ran to Hankich’s destroyed automobile first. The file indicates he thought he heard Hankish – who was still trapped in the car – mutter Lias’ name before running back to his business and calling the police. That’s what he told the cops, anyway.

“But no one could prove it,” Burgoyne said. “I moved to Wheeling three years after that had happened, but I was brought up to speed very quickly. I heard a lot about that bombing and the theories about who could have been behind it. Lias was the popular answer, but there’s a reason why charges were never filed.”

Two of these three bookies have moved on to legitimate businesses, and one is retired from the steel industry. All of them are in their 60s, and they all admitted they are surprised they, too, didn’t go to prison. They agree that their activities didn’t seem like a big deal to the common person in this valley and that it wasn’t until people like Burgoyne and Dick Jones starting poking around when most folks realized they’d witnessed criminal activity for years.

On the Island, and along Market Street in and outside the Sportsman’s, in Center Wheeling, and often in South Wheeling, the action was hot, it was popular, and it was obvious.

“It was out there; that’s for sure, but if you wanted to place any bets, we had to know who you were before you got in,” one of the bookies told me. “It’s still out there. You can still place bets, but it’s invisible now, and no one really cares anymore. And it’s pretty much legal now.”

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.