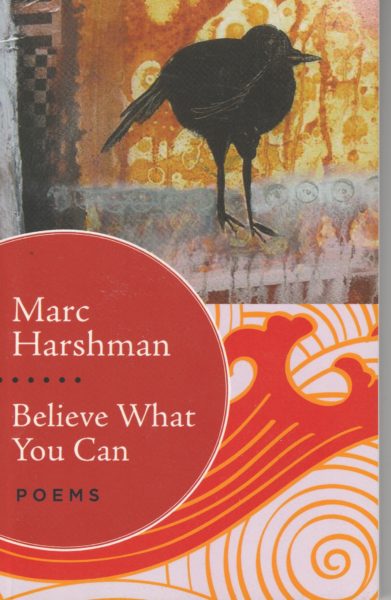

“Believe What You Can,” Harshman’s second full book of poetry, was released on October 1.

For now, anyways, his writing career is focused on poetry again because Harshman’s latest published work, “Believe What You Can,” was released by the West Virginia Press in October. What’s odd though is that these works, like “Coal Country” and “These” and “Recoveries,” are prose pieces that flowed more than a decade ago with an edginess that spewed from his pen.

“A friend of mine used this phrase just the other evening when we were exchanging poems with each other, and after I offered him one that was kind of a darker, edgier piece, he said, ‘I’m just delighted by the way in which you have given yourself permission to say what you want.’ I guess it comes with maturity,” Harshman said. “It was about 15 years ago when I started writing these prose poems, and that darker, edgy thing came into those poems, and I can’t exactly explain it.

“But I am grateful for it, and now I feel more open to it whether or not the form is a prose line or a more poetic line. I guess I just feel freer,” he said. “The poems in the new book are relatively recent, but they were composed before I was named Poet Laureate four years ago, but that freedom continues even now.”

Harshman became the Mountain State’s Poet Laureate in 2012.

‘Arts Laureate’

He writes each day, most often in the mornings but also whenever an epiphanic, intuitive notion provokes an insightful revelation, even if it is just for a solitary moment before it fades for the next commonplace occurrence. And many people reach out to this poet daily; it could be a request for an autograph from a fan two counties away, or a school system hoping for an appearance or two, or a fellow writer hoping for a Harshman endorsement for a piece set for publication.

“It’s work, and it goes on and on, and that’s OK,” he said. “Sometimes I’ll jot down some of what I’ve accomplished and what I do want to accomplish, and I am really pleased about some of the things, and I am really excited about the Wheeling Poetry Series that was instituted at the Ohio County Public Library with Sean Duffy’s assistance.

“We already brought in four major American poets in the last year-and-a-half,” Harshman continued. “And I am also really pleased that West Virginia Public Broadcasting allowed Glynis Board and me to create this show, ‘The Poetry Break,’ which is now airing every month on the third Thursday. I’m thrilled that it’s happened.”

Writer Irene McKinney became the Mountain State’s Poet Laureate in 1994, and she remained in the position until she passed at the age of 72 in February 2012. She, like Harshman, composed poems about West Virginia’s Appalachian landscape and lifestyles she discovered throughout the state’s 55 counties. Soon after her death this Wheeling resident became the Mountain State’s seventh Poet Laureate when Gov. Earl Ray Tomblin appointed him as such.

But there wasn’t a job description offered to him by the governor following the press conference, so, since that very first day, Harshman has been winging it as well as evolving the position more toward, let’s say, an “Arts Laureate” gig.

“No matter where I go, I have people ask me about my role as the state’s Poet Laureate, but there isn’t anything written down, which I appreciate,” Harshman said with a chuckle. “I usually tell them that I see it as my role to trumpet the amazing wealth of artists, and not just writers. There is no Laureate for the other arts, so I feel I might as well do it for everybody while I have the podium.

The state of West Virginia has a web site celebrating poetry from the Mountain State.

“There’s so much going on with literature and painting and music and with all of the other arts. For such a small state about which the nation seldom hears many positive things, the wealth of talent here is really astounding,” he professed. “But it’s not a new phenomenon because the talent level in West Virginia has historically been very good.”

His father was a tenant farmer, and that means there was a fee to pay to work those 60-80 acres, so Pops grew corn and oats and soybean and harvested hogs and chickens. Harshman also was most specific when recalling, “Oh, and there were those five milk cows, too.”

That’s because he found himself in the stereotypical “farmer’s son” role while milking those cows and feeding the chicks and pigs until his father surrendered his passion for farming for full-time factory work.

“But I would pitch hay, and I was surrounded by other kids who were working on their farms until I was almost a teenager, and the influence that environment had on me is still in me because it’s always showing up in my work. But I wasn’t a farmer; that’s for sure,” Harshman insisted. “I didn’t do what my father had to do, and I’ve never been good with any kind of farm machine, and any kind of farmer that is a good farmer can take apart a machine and put it back together.

“But it is there because those experiences colored me,” he continued. “But I’ve never been afraid to help someone pitch hay or to help a neighbor with their butchering.”

Harshman was a teenager during the 1960s, a legendary decade for a musical evolution and flower-child lifestyles, so it’s (impossible) to predict what may be gently blaring from his stereo speakers at any time any day. Might be classical, could be rock, or a visitor may be met by total silence because Harshman does need that, too.

“I tell everyone that if they want to be a great writer, they have to completely immerse themselves in all the arts,” he said. “At least for me they have always fed me. And there’s no one thing; I’d die without rock n’ roll, but I would also die without Beethoven and Mozart. I do have a penchant for several French impressionists composers, too, and there are many other genres that stay with me.

“And I was even taught how to play the guitar by a famous rock n’ roller, and I love to tell this story,” he continued. “The band at the Sock Hop in my little town in Indiana was two brothers and another couple of fellows on bass and piano, and the summer I was graduating high school that band decided to call themselves ‘The McCoys,’ and they recorded a song called, ‘Hang On Sloopy.’

“Rick, the leader of the band, taught me how to play guitar on an old Montgomery Ward guitar,” he added. “Rick would reinvent himself years later, and he took the name, ‘Rick Derringer,’ and he was very successful. And then another decade later I was watching a Cyndi Lauper video, and there’s Rick playing the guitar. So rock n’ roll did make a difference with me.”

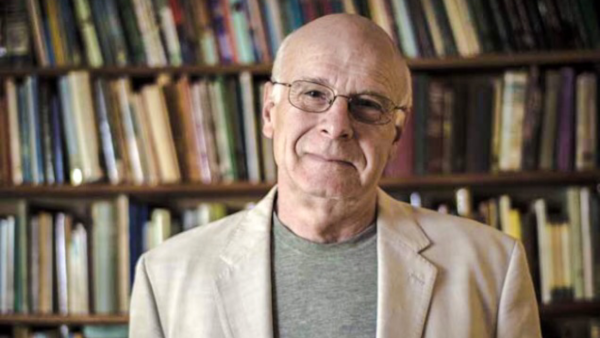

Harshman has spearheaded many education programs all over West Virginia. (Photo by West Virginia Public Broadcasting)

A Writer’s Life

His beautiful wife, Cheryl, is a lady he met soon after arriving on the Bethany College campus in the late 1960s, and she, too, is a writer and visual artist who is native to farm country in southern Lorraine County, Ohio. Once a couple and seeking graduate degrees, they traveled away from the Northern Panhandle and out of the Mountain State, but this pair was determined to return if opportunity made it possible.

“I came to Bethany College in 1969, and I fell in love with this place right then,” Harshman recalled. “I am from Indiana, and as a boy on my father’s farm in flatlands Indiana we could not afford a real vacation, so what we did was hop in the car on a Saturday or Sunday afternoon, and my dad would point the car south.

“After driving for about two hours toward the Ohio River, we would begin to come into hill country in southern Indiana, and we all loved it. We’d stop, get out, and then get into the creeks and pick up flat, limestone slabs to bring back for our mother’s flower garden. It was a heavenly time,” he said. “So when I arrived in Bethany and sawall of these hills, I was thoroughly smitten. That’s where my initial love for West Virginia came from, and even though I left this area for grad school, I was always looking for a way to get back here, and it happened.”

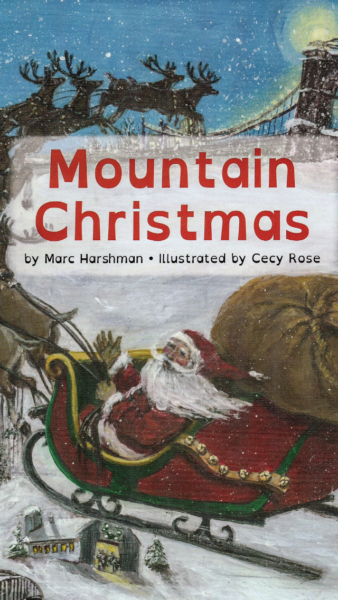

At first his success as a writer was staggered with years between interested publishing companies, signed contracts, and new Marc Harshman releases, but the past 12 months? “Mountain Christmas,” a children’s book complete with illustrations by Cecy Rose was published at this time last year, and during the most recent spring season, “One Big Family” landed on book store shelves, too.

“Mountain Christmas” was released at this time in 2015.

“I wrote that book over 20 years ago, and I sold it 15-18 years ago, but “One Big Family” got lost in a corporate merger,” Harshman recalled. “But I was able to resell it a few years ago, and now it’s out, and I am very happy to see it.

“And then just a few weeks ago the West Virginia University Press published my second full-length collection of poetry (“Believe What You Can”), and I am very grateful to them, and it even has a cover done by my dear wife,” he said. “That’s kind of cool that they allowed that to happen.”

Some peaks, a lot of deep, frustrating valleys, and rejections and second thoughts and wonderment about if and when and why not have consumed the majority of this man’s existence since sending that very first manuscript, and that is why Harshman was employed as a teacher for the public school system in Marshall County until 2001. Once hired, he was assigned the fifth and sixth grades at Sand Hill School, a three-room schoolhouse near Limestone, a small, rural community that rests close to the Pennsylvania border.

Then arrived the thought to his mind that it just might be plausible for him to leave behind the chalk and erasers and grading hand-written essays to focus solely on his very own scribblings.

But is Harshman’s reality what he envisioned while dreaming like a child of the ‘60’s?

“Oh no, I’m very selfish,” he said with a loud laugh. “Nothing is ever enough because I always want more, but I am also mature enough now to look back and say that I can’t really have any deep regrets. I’ve been able to do much of what I wanted to do much of my life, and that’s a gift.

“To hell with the money; to hell with prestige. My years in the classroom, sure they were hard, and they took a big part of my life, but do I regret them? No, because it was a delight to be with those children,” he added. “It feels good to think that I may have helped many of them and that I pointed them in the right direction, and now I am doing other things like living a writer’s life.”

(Cover photo by Steve Novotney)

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.